Talking to children about death is difficult. A lot of us shy away from it, however, when a loved one dies, it’s much trickier to avoid. Learning about death and grief is an integral part of a child’s emotional development, and it is important they have a space where they can process it openly. The Children’s Healing and Therapeutic Services (CHATS) Team at Birmingham Hospice does just this.

Karen Ward has worked at Birmingham Hospice for 24 years. Previously a palliative care social worker when she first joined the hospice, she decided to put her all into the children’s work. Over time it grew, and now Birmingham Hospice has a flourishing team dealing with all aspects of childhood grief. “I’ve been able to implement a lot of things that I wanted to do with the great team that I’m in,” Karen said.

Loss is a part of life. Even when a child has not faced a significant bereavement, they still experience loss and grief. Karen explained: “Pets die, and it hurts. Toys get lost, and it hurts. Friendships break up, friends move away, all sorts of things. With all the transitions that children go through, it’s important for them to understand what grief is.”

CHATS supports children and their families when a relative is using the hospice’s services. They are with them through the journey, before and after bereavement. As Karen said, “we really do get to know the whole family”.

Supporting the children also brings a great deal of comfort to the patients. Knowing their children are in safe hands, even when they are no longer here, is vital in feeling at peace with the situation.

This work includes a variety of activities and sessions to support children and their families. There is emotional support such as one-to-one sessions and peer support groups, where children can chat with others who are of similar ages and situations. Every year around Christmas time, CHATS holds an event called ‘Our little time to remember’, where families and children gather to remember their lost loved ones and share memories. They also provide training sessions for teachers in schools, and parent grief support groups.

CHATS helps children value memories by getting creative. For example, they make memory boxes, memory books and write up stories of their loved ones. Karen said: “One of the things that’s really important with children is that we need to try and capture the memories they have got before they slip away, because they will need them.”

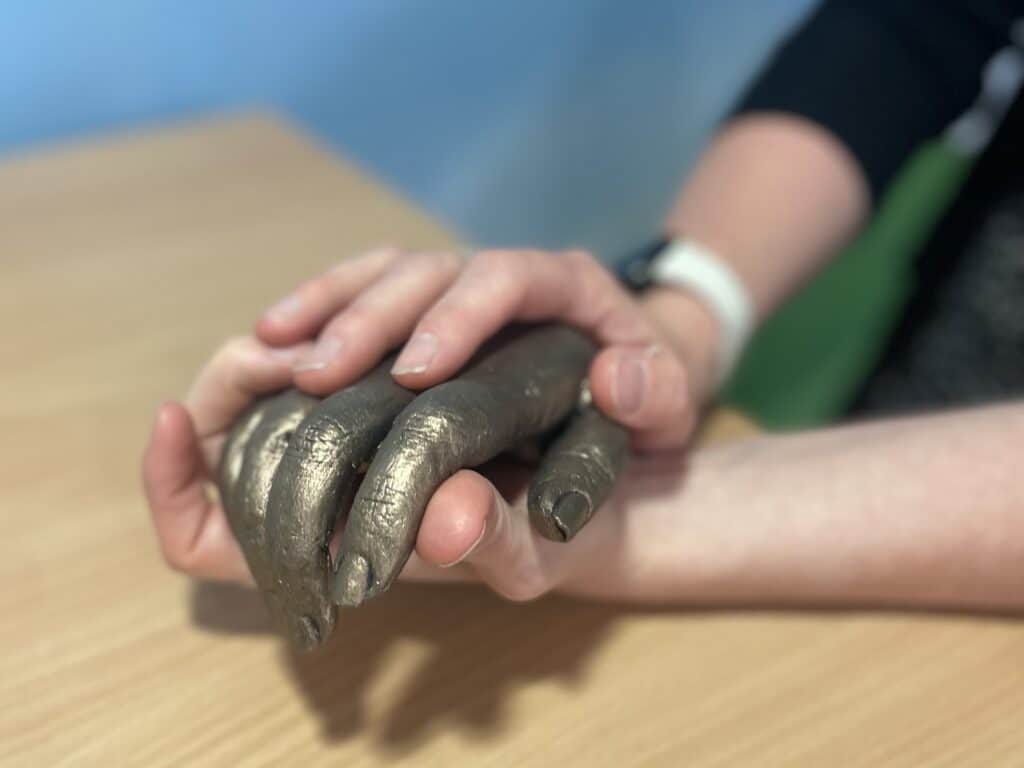

Another significant activity the team do with the children is making hand casts of the patient and their child. While they are holding hands in the cast formula, they are encouraged to have a conversation which the child will remember when looking at it in future. For many of the children and their families, the hand casts become their treasures.

Karen explained: “We encourage them to ask questions like, ‘say what you really love about them?’ or ‘what advice would you give them for when they’re 18?’ For those three minutes, while their hands are in that bucket, they are having this really close conversation. The hope is that after the person has died, they have those hands, and they remember the time when they made that hand cast.”

Karen said that her favourite part of the role remains the one-to-one work with children. “You need to gain their trust,” she said. “They need to know that you are genuinely interested in them. You can’t pretend with children; they see right through you. While talking to them, it is about making them feel like the most important person.”

“Nobody asks children what they think death is. But they have got death going on all around them: on TV and the games they play. Nobody ever really explores that with them.”

She said it was also very rewarding to come up with a new idea and see it help the children in action. “This can be very fulfilling, but it is still a bit of trial and error with ideas because things that work with some children, don’t always work with someone else.”

CHATS helps the children find treasures that they can value forever, long after their loved one has passed away. One of the ways they do this, is by encouraging patients to write letters to their children. While this is a hard thing to do, Karen explained how it would be significantly valuable to the child for the rest of their lives. “I always say to people, if you just write one sentence, or one card, that’s a nugget of gold for your child, for the future, and they will treasure that.”

Working in CHATS shows you that the hospice is part of the community. “It’s not something that sits outside. It is integral,” Karen said. “We belong to them, and they belong to us is the way I like to look at it.”